Why Milk Tea Alliance appeared?

In 2020, in a brief span of time, a notable but informal alliance was formed online across Asia – the Milk Tea Alliance. Members of this coalition are young activists, mainly in Southeast Asia. All have different domestic agendas. However, they have united to deal with the growing threat – dictatorial China’s growing presence in the region.

The alliance started when a popular Thai actor, Vachirawit Chivaaree, star of the popular Asian drama “2gether“, posted on Twitter a photo collection depicting Hong Kong as a country. Thousands of belligerent Chinese netizens have called for a boycott of the Vachirawit show. Vachirawit later apologized, but these belligerent elements found an old Instagram post of her girlfriend Vachirawit with content that seemed to show she supported Taiwan as an independent country. This makes the Chinese militants even angrier.

Soon after, Thai netizens responded with funny photos. The Chinese patriots who responded by insulting the Thai King and Prime Minister, who came to power in a coup, were useless. Thai netizens deftly rejected China’s criticism and won praise from young people in Hongkong and Taiwan, who know very well Chinese repression. They also received cheers from others in Southeast Asia, which resent the rule of dictators, such as President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines.

So this alliance was born, named after the tea-drinking habits prevalent across Asia. In mainland China, tea is not drunk with milk. But Taiwan’s most famous drink is pearl milk tea; Hongkong people drink tea with milk, and Thai brown-yellow tea is sweetened with condensed milk. Since then, other people have also joined. After Indian soldiers died in clashes with Chinese soldiers at the disputed border, Indian netizens added masala tea to the alcohol. And after the military took power in the coup in Myanmar on February 1, pictures of laphet yay, Myanmar milk tea, are flooding social media.

China with main variable Myanmar

The Milk Tea Alliance has not yet mounted or is completely anti-China. Frank Netiwit, a young Thai activist who has been at the forefront of the protests calling for democracy, said the condemnation of China was partly aimed at criticizing the domestic dictatorship. In Myanmar, anger is directed at Governor-General Min Aung Hlaing and the army.

China has long supported regional autocrats. It describes the coup in Myanmar – which waged the arrest of Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s leader, and hundreds of others – as a “major cabinet reform.” China is increasing investment in Southeast Asia and seeking political influence to protect these investments. But the rulers of Southeast Asia were thorny and nationalistic. The local people are angry because they think their leaders are dominated by China.

The Milk Tea Alliance phenomenon underscores the way Southeast Asians often welcome Chinese economic participation, but it is accompanied by other complex attitudes regarding China. Some experts say Southeast Asia is a microcosm of China’s global ambitions – foreshadowing how its diplomats, corporations, and even its armed forces work in other places in the future.

Southeast Asia is undoubtedly the most perceptive of China’s presence anywhere else. Southeast Asia begins where China stopped – in the northern mountainous border areas of Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar. Many groups in the modern ethnic populations of Southeast Asia are of northern origin. The Chinese Empire claimed dominance over the Southeast Asian dynasties. Vietnam, Thailand, and Burma (now Myanmar) are countries with important tributary relationships.

The Left Side of the Belt and Road

Today, the 10-country Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is an important link in China’s supply chain. In the past, China’s economic interactions with Southeast Asia took place mainly by sea. Now that is changing. The industrial hub of China is moving away from the coast, towards the southwest, and on the border areas with Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam. For this new hub land, nearby Southeast Asia is a market, an input supply, and an available route to the sea.

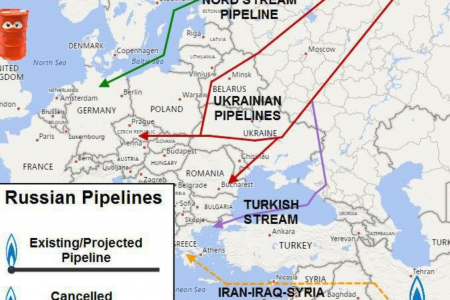

The main obstacle to moving south is the geographic problem – the borderland is insurmountable. To get past them, China has intervened in Southeast Asia with a slew of cross-border infrastructure: new roads, a gas pipeline through Myanmar to the Kyaukphyu deep-water port in the Bengal Bay, and a service. High-speed rail is expected to pass through Laos to connect Kunming with Singapore. Most of these projects are considered part of President Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road” initiative.

However, many Southeast Asians find China is sometimes ever-present and make insincere statements about non-interference. Chinese investment comes with constraints. Banks and construction companies insist on employing Chinese workers. Contracts are often ambiguous and overvalued (some include the bribes required to win a contract).

China-related corruption was a factor in Malaysia’s 2018 election defeat by Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak and his party, which has been in power since independence. Contributing to that failure was the appearance of the Chinese Ambassador openly campaigning for the party of Chinese descent in the ruling coalition – these actions are far more than the declaration of no intervention. Meanwhile, a senior diplomat for the region said tacit grants to political parties in Malaysia and Indonesia are often the entrance ticket for doing business. China is said to have poured money into Duterte’s success in his 2016 bid to become the president of the Philippines.

Several projects backed by China, above all the high-speed rail line for the small and impoverished Laos, have little economic relevance and contain high environmental risks. An unprecedented drought in 2019 in the lower Mekong on the grounds that China built dams that interrupt the river’s seasonal flow, on which the livelihoods of millions of Cambodian and Vietnamese fishermen depend. In Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, Chinese land acquisitions mean deforestation.

China’s peaceful goodwill?

As for China’s coming peacefully, policymakers wonder how to deal with that issue with its unreasonable and contradictory claims in the South China Sea (Vietnamese call it the East Sea), claims that have pushed China into disputes with Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In 2016, in a lawsuit brought by the Philippines, the Arbitral Tribunal rejected China’s claims. When Singapore urged China to comply with the court’s rulings, Chinese diplomats harshly criticized the Singapore government. In contrast, tiny Cambodia, which prioritizes loyalty to China over ASEAN’s solidarity, has been rewarded with loans.

However, giving in to China does not mean getting rewarded. Duterte has set aside the arbitral tribunal’s ruling in hopes of attracting Chinese investment. Xi Jinping has quickly promised to invest billions of dollars in infrastructure. But few investments have come true. Meanwhile, in the South China Sea, China’s aggressive actions are still taking place.

Therefore, this is also the time when Southeast Asian countries need to adjust their policies, especially with China, to avoid being too deeply influenced by Beijing.

Thoibao.de (Translated)